The Debt Dilemma: Navigating the Perils of Loan vs. Credit Card High Interest

Loan Vs Credit Card High Interest In the intricate landscape of personal finance, few decisions carry as much weight as choosing how to borrow money. When faced with immediate financial needs—whether consolidating existing debt, funding a home renovation, or covering an unexpected medical bill—two primary options dominate the field: personal loans and credit cards. Both offer access to funds, but they diverge dramatically in structure, cost, and long-term impact, especially when it comes to interest rates. Understanding the nuances of high-interest loans versus high-interest credit cards is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical survival skill in an economy where debt can either be a managed tool or a path to financial quicksand.

This article will dissect the mechanisms, risks, and strategic uses of both instruments, providing a comprehensive guide to making informed decisions under the pressure of high interest rates.

Part 1: The Anatomy of High-Interest Debt

Interest Rates: The Engine of Cost

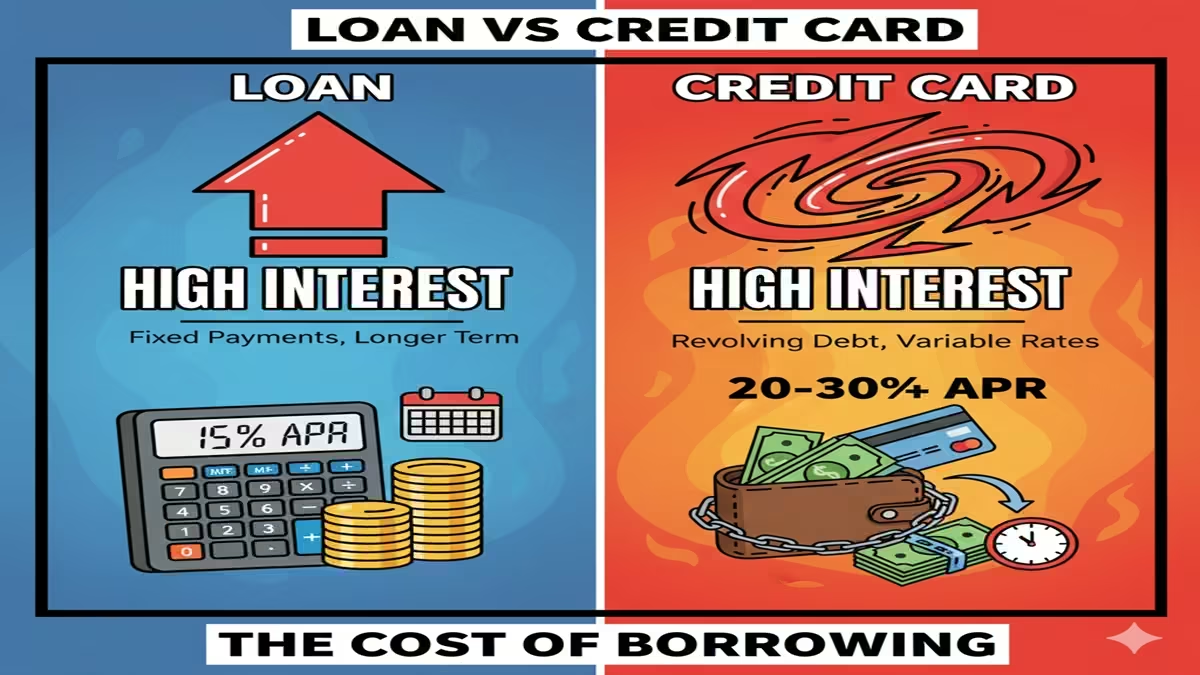

At its core, the cost of borrowing is dictated by the Annual Percentage Rate (APR). This figure includes the interest rate plus any associated fees, providing a true yearly cost. “High-interest” is somewhat contextual, but generally, any APR significantly above the prime rate—currently often anything above 15-18%—enters this risky territory.

For credit cards, interest rates are almost exclusively variable, tied to an index like the Prime Rate. As of 2024, average credit card APRs frequently hover between 20% and 25%, with cards for those with poor credit exceeding 30%. This rate applies to revolving balances, meaning the debt you carry from month to month.

Personal loans, typically unsecured (no collateral required), offer fixed interest rates for the loan’s lifetime. While borrowers with excellent credit can secure rates as low as 6-8%, those with fair or poor credit may see offers from 18% up to 36%, the latter being the threshold often considered “predatory.”

The Structural Divide: Installment vs. Revolving Credit

This is the most fundamental difference. Apersonal loanisinstallment credit. You receive a lump sum upfront and repay it in fixed, regular payments (monthly installments) over a predetermined period (e.g., 3, 5, or 7 years). The road has a clear beginning, middle, and end. The interest is calculated on the declining principal, and the payment schedule is set in stone.

A credit card is revolving credit. You are granted a credit limit, which you can draw from and repay repeatedly. There is no set end date. You are required to make only a minimum payment each month (often 1-3% of the balance), but you can carry—or revolve—the remaining balance indefinitely. This revolving nature is where high APRs become particularly dangerous.

Part 2: The High-Interest Personal Loan: A Double-Edged Sword

The Case For a High-Interest Loan:

- Debt Consolidation Catalyst:This is its most powerful use. If you have multiple high-interest credit card balances, rolling them into a single personal loan—even at a high rate—can be beneficial if that rate islowerthan your current credit card APRs. Converting multiple variable rates into one fixed payment simplifies finances and can provide psychological relief.

- Predictable Path to Zero:The fixed payment and term create mandatory discipline. You cannot extend the loan term arbitrarily (without refinancing). This forced structure ensures the debt has an expiration date, which is invaluable for those who struggle with the open-ended nature of credit cards.

- Lower Potential APR:While still high, a personal loan for someone with mediocre credit will often have a lower APR than a credit card for that same individual. The lender’s risk is bounded by a fixed repayment plan.

The Perils of the High-Interest Loan:

- Front-Loaded Costs:Many personal loans, especially from online lenders, originate with origination fees (1-8% of the loan amount), which are often deducted from the loan proceeds. This means you receive less cash than you borrowed but owe interest on the full amount.

- Rigidity:The fixed payment is a blessing and a curse. In a financial crisis, you cannot choose to pay just the minimum. Missed payments incur severe penalties and damage your credit.

- Risk of Secured Backing:Some high-interest “personal loans” may become secured by your assets (like a car title loan) if you have poor credit, risking the loss of property.

Part 3: The High-Interest Credit Card: A Potential Pitfall

The Case For a High-Interest Card (It’s Slim):

- Strategic Grace Period:If you possess exceptional financial discipline, you can use a credit card and pay the statement balancein full and on time every month. In this scenario, the APR is irrelevant, as you incur no interest. The card becomes a tool for convenience, rewards, and building credit.

- Emergency Buffer:As a last-resort safety net for a true, unexpected emergency when all other options are exhausted, the available credit can be vital. The key is to treat it as a bridge to be demolished (paid off) immediately.

- Flexibility:You control your payment. In a tight month, the minimum payment option exists (though it is a trap to be avoided at all costs).

The Perils of the High-Interest Credit Card:

- The Minimum Payment Trap:This is the engine of the credit card industry’s profits. On a $5,000 balance at 24% APR, a 2% minimum payment starts at $100. If only the minimum is paid, it would take over30 yearsto repay and incur nearly $9,000 in interest. The minimum payment is designed to keep you in debt for decades.

- Compounding Interest:Credit card interest compounds daily. This means interest is calculated on your balance plus any previously accrued interest every single day. This snowball effect makes debt grow alarmingly fast.

- Behavioral Enabler:The ease of swiping, tapping, or clicking can disconnect the pain of spending from the act, leading to balance creep. High limits can create a false sense of financial security.

Part 4: The Head-to-Head Comparison & Strategic Scenarios

Let’s model a concrete example: Managing a $10,000 debt.

- Option A: High-Interest Credit Cardat 24% APR. Minimum payment = 2% of balance.

- Option B: High-Interest Personal Loanat 20% APR for 5 years. Fixed payment = ~$265/month.

The Results:

- Credit Card (Paying Minimum):Time to repay:Forever, effectively.You will barely chip away at the principal. Total interest: catastrophic.

- Credit Card (Paying $265/month—same as loan):Time to repay:~5.5 years.Total Interest:~$7,500.

- Personal Loan (Paying $265/month):Time to repay:5 years exactly.Total Interest:~$5,900.

Analysis: Even with a high rate, the loan’s structure saves significant money and time compared to putting the same debt on a card and making equal payments, because the loan’s amortization schedule aggressively tackles principal. The credit card’s revolving nature, with its minimum payment option, is its most dangerous feature.

Strategic Decision Framework:

- For Debt Consolidation:A personal loan isalmost always superior, provided its APR is lower than the weighted average of your current card APRs. It provides a definitive payoff plan.

- For a Large, One-Time Project with a Defined Budget:A personal loan is better. It delivers the needed sum and imposes repayment discipline.

- For Ongoing, Fluctuating Expenses (e.g., a month of unexpected bills):A credit card offers necessary flexibility, butyou must have a concrete, aggressive plan to pay it off within 3-6 months.If you cannot, do not use it.

- For Emergencies When You Lack Savings:This is a crisis point. A personal loan may offer slightly better terms, but the application process takes time. A credit card can provide instant relief but at a far greater long-term cost. The real solution here is to build an emergency fund.

Part 5: Escaping the High-Interest Trap

If you are already ensnared, action is mandatory:

- The Debt Avalanche Method:List all debts by APR, highest to lowest. Pay minimums on all, and throw every extra dollar at the highest-interest debt (usually a credit card). This mathematically saves the most money.

- Balance Transfer Cards:If you have good credit, transfer high-interest card balances to a card with a 0% introductory APR (for 12-21 months). This creates an interest-free window to pay down principal.Beware:transfer fees (3-5%) apply, and after the promo period, a high rate kicks in.

- Credit Counseling:Non-profit agencies can enroll you in a Debt Management Plan (DMP). They negotiate lower APRs with your card issuers and you make one monthly payment to them. This closes your cards but provides a structured, lower-cost payoff path.

- Debt Settlement:A risky, last-resort option where a company negotiates to settle debts for less than you owe. It severely damages your credit for years and has tax implications.

- Side hustles, austerity budgets, and selling unused items create the cash flow to attack debt directly.

Conclusion: The Mindset of Prudent Borrowing

The choice between a high-interest loan and a high-interest credit card is not about finding a “good” option, but about selecting the least damaging tool for a specific job and wielding it with extreme caution.

The personal loan is a structured, finite marathon—painful but with a clear finish line. The credit card is a deceptive, open-ended quicksand pit that feels comfortable until you realize you cannot escape.

Ultimately, the best strategy is to minimize reliance on both. Use credit cards as transactional tools, paid in full monthly. View personal loans as strategic, one-time instruments for specific goals, preferably at the lowest rate you can qualify for. In a world of easy credit, the greatest financial strength is the ability to walk away from borrowing altogether, fortified by savings and living within your means. When you must borrow, let it be a deliberate, structured choice, not a reflexive swipe into a high-interest abyss.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. I have poor credit and can only get high-interest offers. Is a personal loan or credit card less damaging in the long run?

Generally, a high-interest personal loan is the less damaging option for a one-time, lump-sum need. Its fixed term forces an end date to the debt, preventing the infinite revolving cycle of a credit card. Even at a high APR, the total interest paid on a loan will often be lower than if the same debt were carried on a card where you only make minimum payments. However, your priority should be to improve your credit score (by making all payments on time) to refinance to a lower rate as soon as possible.

2. What’s more harmful to my credit score: a high-interest personal loan or maxing out a credit card?

Maxing out a credit card is typically more immediately harmful. A key factor in your credit score is “credit utilization”—the percentage of your available credit you’re using. Exceeding 30% on a card, and especially maxing it out, severely dings your score. A personal loan doesn’t affect utilization in the same way. Both, however, will hurt your score if you miss payments. A loan adds to your “credit mix,” which can be positive, but the hard inquiry and new debt will cause a temporary dip.

3. Can I use a high-interest personal loan to pay off high-interest credit card debt?

Yes, this is a common and often wise strategy known as debt consolidation. It only makes financial sense if the loan’s APR is lower than the average APR on your credit cards. The major benefits are: 1) You replace multiple variable, high rates with one fixed, (hopefully) lower rate. 2) You simplify multiple payments into one. 3) The installment structure guarantees a payoff date. Critical Warning: You must close the paid-off cards or practice extreme discipline not to run up new balances on them, or you’ll end up with both the loan and fresh credit card debt.

4. Why is the minimum payment on my credit card so dangerous?

The minimum payment is calculated to be just enough to cover the accrued interest for the month plus a tiny sliver of principal—often as little as 1%. At a 24% APR, you are barely keeping pace with the interest. This design keeps you in debt for decades, turning a modest purchase into a cost that is multiples of the original price. It is the primary mechanism by which credit card companies generate profit from cardholders who carry balances.

5. Are there any situations where choosing a high-interest credit card is the better option?

Only in two very specific scenarios:

- You can and will pay the balance in full before the due date.In this case, the APR is irrelevant, and the card may offer rewards or buyer protections.

- As a last-resort emergency fund for a truly unexpected, urgent expense(e.g., a critical car repair to get to work), and you have a guaranteed plan to pay it off within a few months. Even then, exploring a loan from a credit union or family should come first. The credit card should be the final stopgap, not the first resort.